Intensive Care from an old anaesthesia physician's point of view

Intensive care was the task, which was closest to our hearts. We were

dedicated intensive care physicians.

But we did not understand how this work pulled us away from the normal reality. Slowly, we had been forced into God's backyard where we had no permission to be.

Our normal thinking about right and wrong, our Christian ethic, was no longer applicable in the intensive care unit.

The effective modern intensive care developed rapidly in the late 60's.

Previously, we could see old patients with femur fractures die because of minimal bleeding and the obstetric patients with major bleeding they died before our eyes. It was God's will. It was natural. Patients with severe infections died quietly on the same day they came to the hospital, young or old.

What we thought was true was how easy the old patients got heart insufficiency if they got too much fluid intravenously. Fluid should therefore always be given very carefully and slowly. And we knew for certain that because the blood pressure dropped when the patient became severerly ill it must be important to raise the pressure to normal again

With Norepinephrine we contracted the vessels. And cold, sweaty and white as snow the patients slipped away into the death. Year after year. The Second World War, The Korea war, hundred thousands of pale and cold soldiers dying. And those who survived the bleeding, they were killed by the renal insufficiency.

Why didn't we understand? To contract the blood vessels was the nature's own way to solve the problem of blood loss: and that was appropriate to small losses of blood. But it did not function in massive ones. In that case God was no longer interested in survival and therefor the body reacted in a wrong way.

In the late sixties the revolution of the intensive care came on. The man outwitted God. It was not the strangulation; it was the dilatation of the vessels that was the key to the problem. The patients survived even though the blood pressure fell. This was the first step. Then came the treatment with saltwater, the central venous pressure, warm blood and the knowledge which made us loose the fear of giving too much fluid. We drowned the patients in the water of ancient oceans and the bleeding women from the obstetric clinic survived. What an enormous satisfaction.

After that came the ventilators and the intravenous nutrition.

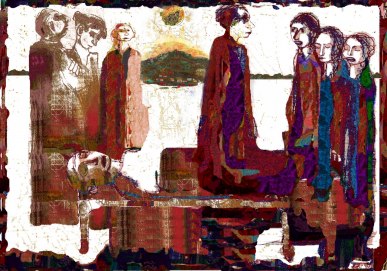

The intensive care brought us into a foreign country. Our ship sailed up the river, farther and farther into an unknown nature. All emerged with lightning rapidity. The deepest hidden mysteries of life were to be solved. We nursed our patients as precious plants and we took over the functions of the organs, one after the other. We held the life in our hands; we were the explorers of the new age. Into the hidden and the forbidden regions of life.

Maybe God got angry. Or he hovered silently in space and bided his time. Or was he grieved?

Something went wrong and nature fought back. We stood there helpless.

The patients survived in our ventilators. Our drugs, our fluids and our care governed their life functions.

But inside their bodies they were eaten up by infections and by new diseases that we ourselves had created, which had never existed before.

Nature retaliated with blind fury: the blood-clotting system was destroyed, the lung tissue petrified. And finally an empty shell, while the families of the patients were breaking down in despair.

The same deterioration happened to the staff that were treating the patients with utmost care, but in vain. Treating patients who had no possibilities to come back to any kind of life.

What should we do? We were stuck in a trap. We should stop the treatment but could not because we had lost the ability to make reliable prognosis. We could not tell anymore wich ones would slowly die undignified and which ones would survive. Whatever we did was wrong.

No ethics or morals were capable of helping us.

This is an inescapable part of reality in an intensive care unit. And with a sadness and as a constant reminder of our insignificant role in maintenance of life, we have to live on and work with this knowledge.

It is the inheritance of modern intensive care

It is a sad story but there is another side of the development: methods become more and more advanced. Forecasting ability better. Care increasingly perfected. What meant a certain death not so long ago is now a commonplace. In the records we barely even note the fast shock treatments, the few hours of ventilator support, the advanced post-operative monitoring of an 80 year-old patient. But that is the difference between life and death.

And it's all over in a few hours and the patient is back in the ward. Trifles, we think. Yes, but without the experience and the knowledge we got from the failures of the many heavy, sad human cases that died in our department, those many patients who now pass the intensive care units would not have survived.

Hans Huldt